Why is aperture measured in f-numbers?

Scientific research pinhole lens

08/21/2025

Low distortion rectilinear M12 S-mount board lens

08/21/2025If you’ve ever adjusted your camera’s aperture settings, you’ve likely noticed the sequence of numbers: f/1.4, f/2.8, f/4, f/5.6, and so on. These seemingly arbitrary values, known as f-numbers, are the backbone of aperture measurement in photography. But why are they used instead of simple millimeter measurements? The answer lies in physics, mathematics, and the need for a standardized system that works across all lenses and cameras. Now, Why is aperture measured in f-numbers?

1. The Birth of F-Numbers: A Mathematical Solution

The concept of f-numbers dates back to the early days of optics, when scientists needed a way to describe the light-gathering ability of lenses independently of their focal length. The “f” in f-number stands for focal length, and the number itself represents a ratio:

F-number (N) = Focal Length (f) / Diameter of the Aperture (D)

For example, a 50mm lens with an aperture diameter of 25mm has an f-number of f/2 (50 ÷ 25 = 2). This ratio is crucial because it ensures consistency. A lens with a focal length of 100mm set to f/2 will have an aperture diameter of 50mm, allowing the same amount of light to enter as the 50mm lens at f/2. Without this standardized system, comparing lenses would be chaotic, and exposure calculations would vary wildly.

How Aperture Influences Sharpness

2. F-Numbers and Light Control: The Inverse Square Law

One of the most critical reasons why aperture is measured in f-numbers is their relationship with light intensity. The area of the aperture (where light enters) follows the inverse square law: doubling the diameter quadruples the light intake. However, f-numbers are designed to simplify this relationship.

Each full f-stop (e.g., f/2.8 to f/4) represents a halving of light, while moving the other way (e.g., f/4 to f/2.8) doubles the light. This logarithmic scale allows photographers to adjust exposure predictably without complex calculations. For instance:

- f/1.4 lets in twice as much light as f/2.0.

- f/8 lets in one-eighth the light of f/2.8.

This system is so intuitive that even beginners can master exposure adjustments quickly. Recommended Reading: Prime lenses with fast aperture for videography

3. Depth of Field: The Creative Power of F-Numbers

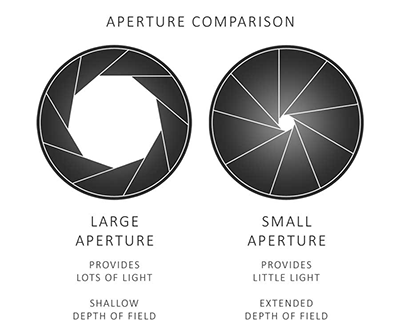

Aperture isn’t just about light—it’s also a powerful creative tool. F-numbers directly control depth of field (DoF), or the range of sharpness in an image. Lower f-numbers (e.g., f/1.4) produce a shallow DoF, ideal for portraits with blurred backgrounds. Higher f-numbers (e.g., f/16) increase DoF, keeping more of the scene in focus, which is perfect for landscapes.

The f-number system’s consistency ensures that a setting like f/2.8 will produce similar DoF effects across different lenses, assuming the same focal length and distance to the subject. This predictability is invaluable for photographers who rely on precise control over their images.

Wide aperture lenses

4. Historical Context: Why Not Millimeters?

Before f-numbers became standard, lens manufacturers used absolute aperture diameters (in millimeters) to describe light intake. However, this method was flawed because a 50mm lens with a 25mm aperture (f/2) and a 100mm lens with a 25mm aperture (f/4) would behave differently despite having the same physical opening. The f-number system resolved this by accounting for focal length, ensuring uniformity.

5. The F-Stop Sequence: Why It’s Not Linear

The f-stop sequence (f/1.4, f/2, f/2.8, f/4, etc.) might seem random, but it’s based on the square root of 2 (≈1.414). Each step represents a 1-stop change in light, and the sequence ensures that each f-number is mathematically consistent with the previous one. For example:

- f/1.4 × √2 ≈ f/2.0

- f/2.0 × √2 ≈ f/2.8

This geometric progression is why intermediate stops like f/1.8 or f/3.5 exist—they offer finer control over exposure and DoF.

6. Modern Implications: Digital Cameras and F-Numbers

Even in the digital age, f-numbers remain essential. While sensors and image processors have evolved, the physics of light haven’t changed. F-numbers still dictate how much light reaches the sensor, influencing exposure, noise, and creative effects. Additionally, advanced features like variable aperture lenses (e.g., 24-70mm f/2.8-4) rely on f-number consistency to maintain predictable performance across zoom ranges.

7. Common Misconceptions About F-Numbers

Many beginners assume that a higher f-number always means better image quality. While smaller apertures (e.g., f/16) increase DoF, they can also introduce diffraction, a softening effect caused by light bending around the aperture blades. Conversely, very low f-numbers (e.g., f/1.2) may produce sharper images but are harder to focus precisely due to the shallow DoF. The key is finding the right balance for your creative goals.

Best aperture lenses for low-light photography

8. The Future of Aperture Measurement

Will f-numbers ever be replaced? It’s unlikely. While alternative systems like T-stops (used in filmmaking to account for light transmission losses) exist, f-numbers are deeply ingrained in photography’s language and technology. Even mirrorless cameras with electronic viewfinders display f-numbers prominently, reinforcing their importance.

Conclusion

The question “Why is aperture measured in f-numbers?” has a multifaceted answer rooted in physics, mathematics, and practicality. F-numbers provide a universal, consistent way to measure light intake, control depth of field, and compare lenses across brands and formats. Without this system, photography would lack the precision and creativity that make it such a powerful art form.

Next time you adjust your aperture, remember that those f-numbers represent centuries of scientific innovation—and a tool that empowers you to capture light in ways no other system can.